Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

Talia Chetrit wants you to know that her partner, Denis, doesn’t normally bottle-feed their son while wearing a Gucci bondage harness. Nevertheless, she understands the confusion. Chetrit is a photographer who has often made herself and her family the subjects of her work, which would seemingly situate her in a lineage of diaristic artists such as Sally Mann and Elinor Carucci. But she told me recently, when I visited her studio, in upstate New York, that she considers all of her work “pure fiction.”

“Boob Top,” 2023.

“Breaker (Chain),” 1997/2023.

Chetrit, whose first solo museum show in the United States is now on view at the Wadsworth Atheneum, in Hartford, Connecticut, has had what appears at first glance to be a peripatetic career in photography. In addition to her self-portraits and pictures of her family, she has done moody, telephoto street photographs, optically tricky still-lifes, and slick fashion shoots. She has even dived into heady conceptual waters, exhibiting photos that she made in high school, which take on poignant layers of meaning in retrospect. Ultimately, however, her disparate work is part of a unified quest to pick apart and play with photographic conventions and, by extension, to poke holes in our expectations of what an image can reveal or hide.

“Mom and Dad,” 2023.

Born and raised in Washington, D.C., Chetrit recalls that she was “out of the womb calling myself an artist.” She started making pictures as a teen-ager, setting up a darkroom in her parents’ laundry room and taking over a custodial closet at her high school. But she claims, in characteristically elusive fashion, that she was “never interested in other people’s photography.” It was only later, while studying at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, that she came to the conclusion that her ideas were better suited to the medium. The pictures that she made in high school, and later repurposed, were by no means virtuosic. They were, for the most part, exactly what you would expect. There is a pouty self-portrait in a short tennis skirt that radiates both childish petulance and budding sexual awareness. In her photographs of friends, some subjects practically vibrate with adolescent awkwardness, and others melodramatically perform their angst. A nude portrait of two female friends strikes a tenuous balance between discomfort and half-understood sensuality. Seen now, the power and the charm of this early work spring directly from its guilelessness. Other photographers have attempted to capture the essence of girlhood directly—Mann, for instance, in her stunning, controversial series “Immediate Family,” or Justine Kurland in her more allegorical, cinematic “Girl Pictures.” But Chetrit’s novel act of self-appropriation delivers truths by way of her younger self’s ham-fisted attempt to conceal them.

“Self-Portrait (Corey Tippin Makeup #1),” 2017.

Another group of images from those days presaged Chetrit’s interest in photographic fiction. In them, her friends play dead, the victims of made-up murders that look simultaneously grisly and unconvincing. (In one, a victim is pictured slumped against a door, her bloodied hand resting on a piece of paper so as not to dirty the floor.) The pictures make me think of Weegee’s sensationalized crime-scene photos, and of our culture’s ghoulish obsession with true crime. I think of the horrors of school shootings, and the pictures of their aftermath that never reach the public eye. I think of the images of children killed in warfare, pushed onto our social-media feeds. For a teen-age Chetrit, however, the constructed scenes were mostly a way to make pictures that weren’t boring. She told me, “ I had this breakthrough moment in high school where I was, like, ‘Oh, I don’t need to wait until my life becomes interesting.’ ”

“Hard to Title,” 2019.

Chetrit has never let go of the idea that photography can be used to create an illusory world outside of our humdrum day-to-day. In her mature pictures, she almost seems to be daring you to believe that she is telling the truth. Some of them, like an image on view at the Wadsworth of Chetrit holding her son to her chest immediately after giving birth, have the unmistakable flavor of intimacy. They are what you might expect from a photographer who is intent on bringing the viewer close and getting “real.” But others, like her series of deadpan “bottomless” self-portraits, for which she poses for the camera nude from the waist down, or a pair of lighthearted pictures of her and Denis having sex in a bucolic field that are intruded upon by the sinuous black line of the camera’s cable release, feel more like a burlesque of intimacy. Chetrit seems to be mocking our desire for self-exposure without actually divulging much. She told me that she started making her sex pictures soon after she and Denis began dating, as a kind of “test” to see if he would be “willing to be there in my work.” She went on, “That wasn’t our sex life. That was our sex life with a camera, and what the camera did to our sex life and our relationship at the time.”

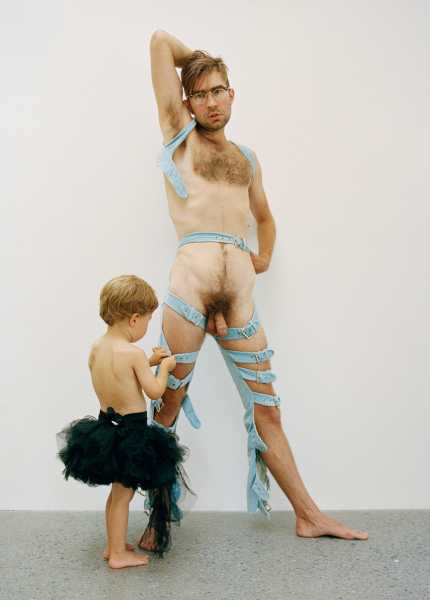

“Buckle (Pam Hogg),” 2023.

Chetrit’s editorial work has allowed her to play around with designer clothing, like that Gucci harness, which she gets on loan from various stylist friends and collaborators. She takes obvious pleasure in dressing Denis in an array of high-end womenswear and edgy, bondage-inspired kit, and in the provocative strangeness of, say, juxtaposing the legs of her infant son with a pair of glossy, thigh-high stiletto boots. For a series of photographs, she invited the makeup artist and Andy Warhol associate Corey Tippin to do her up in his signature clownish style. In an image, Chetrit appears with a stocking stretched over her garish face, like some perverse mashup of a china doll and a bank robber. You get the sense that she views making a photograph the same way a child views playing dress-up: as a chance to stretch the boundaries of the possible.

“Jean Shoe,” 2021.

“Shoe / Trash,” 2022.

Even if Chetrit considers her work “pure fiction,” her images sometimes betray the eye of a documentarian. A picture of her son, adorably flailing on Denis’s chest, with a foot pressed against his father’s stubbled chin, is a stirring, unfakeable portrait of family life. In her pictures of Denis, no matter how ludicrous or stagy, it is impossible to conceal that he is her willing, often joyful, accomplice. (She told me that his reaction to her more outlandish requests is always: “What? No! O.K.”) Similarly, her pictures of her parents exude their supportive gameness, and touchingly expose their affection for each other. Her self-portraits, which stray intentionally into self-objectification, have a sneaking air of defiance, like one she took while pregnant, naked and straddling a mirror with her camera pressed to an eye. Chetrit’s photography asks us to reflect on the imaginary worlds that images create. But sometimes, even through the fun-house lens, small truths, like love or self-love, can be glimpsed.

“Self-Portrait (Downward),” 2019.

Sourse: newyorker.com