Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

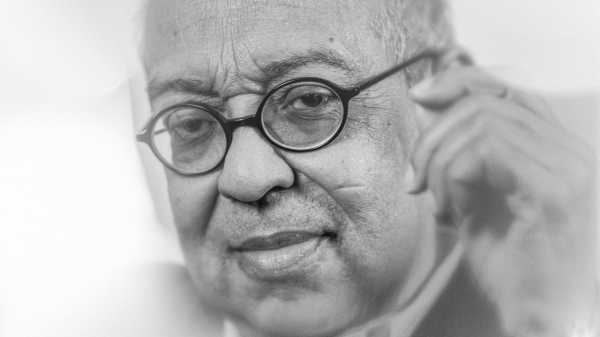

“If that shit don’t work, I don’t wear it,” the director and writer George C. Wolfe told me when we spoke last month. He was talking about the baggage of childhood and the aftermath of his early life in a small, segregated Southern town, but he might just as easily have been talking about his approach to art. Wolfe, sixty-nine, a titan of the American theatre, writes and directs plays and films with an exuberance that feels like the product of freedom unfettered by obligation. He always seems, by the evidence of his work, to be having fun.

In August, at the Martha’s Vineyard African American Film Festival, I had watched from the audience as Wolfe, wearing a sand-colored suit and sneakers, talked with the MSNBC journalist Jonathan Capehart about his new film, “Rustin,” which takes as its subject the great and somewhat undersung civil-rights leader Bayard Rustin. Onstage, Wolfe sat back easily in his chair as if it were a loveseat in a friend’s living room. All self-acceptance, he smiled through clips from the movie as they played, clearly gratified by the results, and sharpened his answers into quips that he knew would get laughs from Capehart and the crowd.

Wolfe is a Zelig of the performing arts in the United States. Born in Frankfort, Kentucky, he earned early acclaim as a writer with plays such as “The Colored Museum” and the musical “Paradise!” His first major hit was “Jelly’s Last Jam,” a musical about the jazz pianist and bandleader Jelly Roll Morton. That early work had a spiky wit and a loopy, slightly campy, intelligence—hallmarks of Wolfe’s style ever since. At the same time, the restless multi-hyphenate—versatile as a matter of course, perhaps because of his early academic training in musical theatre—gained even greater renown as a theatre director. He directed the première production of Tony Kushner’s epoch-defining “Angels in America,” Kushner’s musical “Caroline, or Change,” and Suzan-Lori Parks’s Pulitzer Prize-winning masterwork “Topdog/Underdog.” After Wolfe assumed the artistic directorship of the Public Theatre, he created and directed the popular musical “Bring in ’da Noise, Bring in ’da Funk.”

In 2004, Wolfe embarked on yet another parallel career, as a film director, starting with “Lackawanna Blues,” an adaptation of Ruben Santiago-Hudson’s autobiographical play of the same name. Since then, he’s directed films such as “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks” and “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom,” often bringing to the medium a rhythm, ardency, showmanship, and intensity that seem borrowed from musical theatre, his first love.

His new film tells the story of the March on Washington from the perspective of Rustin—played by the enigmatic Colman Domingo—who conceived of the march and organized it down to its minutest particulars. The film has a surprisingly light tone—it often feels like the story of a caper instead of one of the most solemn civic events in the history of the nation. It opens with a long, kinetic tableau that introduces a wide range of historical personae, including the congressman Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., (Jeffrey Wright) and the civil-rights activists A. Philip Randolph (Glynn Turman) and Roy Wilkins (Chris Rock), and culminates in a temporary betrayal of Rustin—who was considered a liability to the movement by several other leaders because of his sexuality—by Martin Luther King, Jr., (Aml Ameen). “Rustin” is a film enthralled by organization and process, as interested in the workings of institutions—such as the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE)—as it is in the long shadow cast by individual figures such as Rustin, King, and Ella Baker (Audra McDonald).

You might think of “Rustin” as a marriage of the many pet interests and intellectual currents that have coursed through the decades of Wolfe’s career—the civil-rights movement and its afterlives, the gay experience and the disguises that have helped it survive, how a plan comes together almost musically and culminates in a big show. I talked with Wolfe about the film, the contours of his coming of age, and what it takes to keep moving in the world of entertainment and art. Our conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

Watching “Rustin,” I got to thinking about your relationship to biographical narratives, going back to “Jelly’s Last Jam.” Is that a favorite form? How have you approached what we call the bio-pic, and working through the time line of a life?

I hate the concept of the bio-pic. To me, theatre is about ideas. And so, with “Jelly’s Last Jam,” I was intrigued by the idea that someone who, culturally and behaviorally, seemed to be so Southern, and so Black, kept on saying, “My ancestors came directly from the shores of France.” That contradiction was astonishing to me, and I wanted to explore that. And the more I got into that world, the more interested I became in exploring New Orleans. Jelly Roll Morton’s career was so interesting because he travelled from the South to Chicago but, by the time he arrived in New York, Louis Armstrong had arrived—so the best of New Orleans had already been incorporated into the scene. I was intrigued by somebody showing up in the city that made careers too late. The person becomes an idea.

With Bayard, I was fascinated by the summer of 1963. Three months later, J.F.K. is dead. By ’64 or ’65, CORE has turned into CORE East and it’s become more militant. And so there is this doorway, historically, where nonviolence is going to be called into question; the country is going to become more violent. And then you had this brilliant organizer, who was gay—and unapologetically so, for 1963—who put this march together, in eight weeks. The film became a chance for me to not only live inside the character but live inside this time period, and to explore this monumental event, where the country came together. It came together, and then rupture happened for a very extended period of time. That was fascinating to me. Plus, Bayard is just an extraordinary case study.

I become obsessed with people. I was obsessed with Ella Baker, so, I think, Let me put her in here and make sure she’s significant. Ruby Doris—I’m obsessed with her—also a figure in the civil-rights movement, who went to Spelman and then got expelled and was this important figure at SNCC, and she ended up having a child and became a Black nationalist and died by the time she was twenty-six. I become obsessed with certain people’s lives, and the brilliance they are able to achieve in such a short amount of time.

Is there any tension between the ideas that you’re trying to put forward and the things people sometimes want from movies about historical figures—a kind of verisimilitude, perhaps, as though they’re getting a snatch of pages from a history book?

I got a double M.F.A. from N.Y.U., one was in dramatic writing and one was in musical theatre, and every day the other people in the program would say, “Do I like that character? Is that character likable?” and I went, “He’s fucking human.” Those qualities to the best of my ability will go on the journey, and so I have an aversion to this “likable” equation—even though I think Bayard Rustin was an incredibly likable person. Because, if characters are human, they’re more like me, and they’re more like us. It’s why I love the first scene, with Martin Luther King, because he does a shitty thing: he betrays his close friend. He redeems himself later, but I love all of that—because then they’re people. And I can watch it, and think, Let me find my way inside of that story, and, if they can overcome their shit, I can, too. The monument thing—I’m not interested in that.

In this movie, you have an obviously magnetic person whom people flock to, and who flocks to other people, but you do see his flaws always coming back to the fore. As a director, how do you guide an actor like Colman Domingo through that arc? Is there a focus on archival stuff, how Rustin actually moved and talked? Do you rely on diaries?

Colman went on his own journey. He did his own technical research. Like, Bayard was a tenor, Coleman’s a baritone, so he did all that adjustment of his speech. Then the work happens in interpersonal dynamics—that dynamic between him and Ella Baker, say. What’s the power dynamic here? Who is A. Philip Randolph? Who is Martin Luther King at this point in time? Do you think you’re smarter than him?

I rehearse two weeks before we shoot, and every day before I film anything I have a rehearsal period. I clear the entire set, and the actors and I get to work exploring what the scene’s about—blocking it and doing all those things, but also creating a structure of safety so the actors are capable of maximum vulnerability. You’re layering in the truth of the character and all the work that they’ve done, and then you’re sitting at a table and you’re looking at Colman Domingo, and the power dynamic and where that shifts. What is she pushing at? What does she say that nobody else can say? What impact does that have? You’re exposing the character, so that, when a moment of intensity happens, the actor is receiving it in a startling way, and you’re watching a spontaneous moment.

One of my anthems is that an audience can tell when actors are doing something that was discovered just for this movie and when they are recycling some shit from another film. The goal is to have a film where it’s endless second upon second upon second of naked discovery.

Not every film director focusses as intensely on rehearsal as you do. Does that come from your background in the theatre?

It’s part of that. But also it’s how you evolve a vocabulary with an actor—it’s how you get them to go on the journey. You ask questions. Sometimes I’m asking questions not to get the answer but to see where actors are in their process. When we did “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom,” every day—literally—Chadwick Boseman came up to me and said, “Thank God, we had those two weeks of rehearsal.” It’s a grounding period, which then can give way to the unknown, to the vulnerable, to the surprising.

Meryl Streep told me that when she did “Sophie’s Choice,” they would rehearse every morning and then they’d shoot in the afternoon. It gives actors a sense of command, and that command frees them to be open to the material, and to the character’s vulnerability. So it’s not a matter of impersonating theatre—it’s a process, I think, of crafting a scenario whereby brilliant work is possible.

Are there elements of the director’s art that you do in the theatre but that are not portable to the screen?

I reduce it all to storytelling. Sometimes I tell a story and it ends up in an old Victorian building with people sitting too close to one another, and sometimes there’s this little machine that’s recording everything. The equation of intimacy, and how much you capture that intimacy, varies, but you and the actors are always searching for absolute truth. That’s the mission you’re on, and I think that supersedes everything.

In rehearsals for theatre, you’re helping the actor to build muscles so that you, as a director, are rendered inconsequential, so that they can go out there every night and be in charge of their own performance. In film, you’re trying to capture as many different moments, and as many variations on those moments, as possible, so that when you end up in an editing room, you have a vast vocabulary that you can mine, and you can tell the story that you want to tell. Does that make sense?

It does.

I’ve always thought that your film career has drawn especially on your experience in musicals. Not only are your movies often about music on some level but the rhythm and the pacing and the dynamics in them are musical. In “Rustin,” people sing freedom songs, and there is a musical logic to those scenes. Bayard Rustin, of course, recorded his own music. How did you think about those moments?

Directing musicals cultivated the mental muscularity that trained me for doing film.

Really?

Musicals are beasts. They’re beasts. Larry Gelbart, who co-wrote the TV show “M*A*S*H,” said, “If Hitler’s still alive, I hope he’s out of town with a musical.” When you’re in previews, you’re running a town; then you stop, and the crowd comes in, and they’re hostile—or they’re excited, depending on the quality of the work that you’ve done. Sometimes, if you change something ever so subtly, it alters their perception. It’s a good training ground for evolving one’s analytical skills about material, and what works and what doesn’t work.

With “Rustin,” very early on, talking to Branford Marsalis, I envisioned this 1963 jazz quartet. Jazz, to me, in addition to maybe snapping your fingers to it, is cerebral, and I was dealing with incredibly smart men and women. I wanted the audience to know exactly where they were, and to capture that I was dealing with—in many respects, not exclusively—a Black intelligentsia. I wanted them to understand that rhythm. Also, with this quartet—which turned out not to be a quartet, it’s much larger than that—you would have the primary soloist Bayard.

In the opening sequence, the music is hurling you toward the betrayal. You’re being hurled there because these characters are being hurled there. In the scene in Pasadena, Bayard has been the primary soloist, and all of a sudden the word “Pasadena” has a potency, and it renders him silent. Then there’s a new person who’s taken over the room, who feels as though it should be his movie, which is Adam Clayton Powell, and he’s taking the solo. Then, in that absence, Dr. Anna Hedgeman sees Bayard in peril, and this shit’s been bothering her, so she’s taking over.

These people are trying to scramble to drive the music until A. Philip Randolph, who is warm and congenial and evolved, erupts, and ends Adam Clayton Powell’s command of the moment. Because Adam Clayton Powell had issues historically with Martin Luther King. That’s his issue with Bayard: he’s a New York guy. I don’t think Adam cared who did sex with what—it’s just that he’s from New York, so whatever.

Powell thought he should’ve been in charge.

Exactly. He was a politician, and a very smart man, and very successful—he’ll use anything to get what he wants. But A. Philip Randolph steps in and ends the composition.

The sophistication of a jazz combo was very important to me, because it marries the thought processes and the language of these brilliant human beings. All the language of the songs of the civil-rights movement came from slavery. “Ain’t going to let nobody turn me around, going to keep on walking, going to keep on talking, marching up to freedom land.” There is a classic Black American vocabulary that’s in play. And then there is this modern sound that is ever-evolving and challenging and looking for the truth and questioning everything that has come before. And so you have jazz and this traditional sound working together.

Then I was interested in exploring, for lack of better words, hiding in plain sight, as many homosexuals have done. So that, after Bayard has been beaten, you hear this scream, and certain people working on the movie didn’t like it, but I said, “I love that scream.” When a Black person in the South was being beaten, no one heard that scream.

So there’s the scream, and the next beat goes, and keep it moving, go on to the next page, you remember a moment of pain, now you, Bayard, go renew your relationship with your friend Martin.

There’s more than one moment in this movie in which somebody has to swallow their pride because there’s something bigger on the line; the time was so urgent and the mission was so big. This is less a filmmaking question than a personal question, but where does that pain go?

That’s a very interesting question. Probably the most intimate thing that I responded to about Bayard had to do with the idea that, when you are in charge, nobody cares if you’ve got a cold, nobody cares if you’re tired—you’ve just got to deliver. “My closeted boyfriend, who’s got a wife, just broke up with me. Strom Thurmond just outed me on the radio. O.K. Got to deal, keep on, keep on, keep on.” Because you’re building something that’s bigger than you. One of the most moving moments for me is when Rustin confronts Martin Luther King, and then comes back to the office. It’s very conceivable all those kids could run, because being associated with Bayard, this gay man, could blow up in their faces. But he sees them working, and that’s the justification for continuing to work despite such amazing adversity—that you made something bigger and better and stronger than your doubt or your fear.

The question is what happens to the loss and the pain. That’s a very real question. I had a kidney transplant while I was running the Public Theatre, because I was working myself to death.

Did you ever get a chance to stop and think about that?

I wouldn’t be here today if I didn’t. It was a chance for me to realize my body is not something that is there just to obey my will, I have to obey my body as well. Because that was my concept of my body—like, O.K., let me go move this wall, come on, body. And my body was saying, “Excuse me?” Those moments happen so you can redefine and reassess, so that you can keep doing what you’re doing, hopefully in a smarter and more compassionate way, not just more compassionate to other people but to yourself.

This movie seems to me, on some level, to be about the unfinished work of the civil-rights movement. You mentioned a moment when Dr. Anna speaks up and says, “Hey, you know there’s no women here, right?” And, of course, there’s also the homophobia that suffuses the whole movie and is directed toward Bayard.

I’d be remiss if I didn’t ask you whether you yourself felt that growing up, in Kentucky. You went to a Black college, you went to a Rosenwald School—you’re a beneficiary and a product of so many of these movements. And you’re also an out gay man.

I got the benefit of being a part of this incredible community, and then I had to run to become me. It was a very nurturing community, but it also had . . . There was this man, I mention him all the time, a man named Jackson Robb. There was a march on Frankfort, with Martin Luther King, and King stayed at Jackson Robb’s house. Jackson Robb was an undertaker, and he was gay. Wasn’t nobody going to complain about Jackson Robb if they wanted their relatives buried.

But, in terms of my career ambitions and who I was, I had to leave. I went to California, to Pomona, and then, after California, I moved to New York, so that I could claim all of me. But I had to get out of there. I go back and they’re proud of me, and I’m happy that they’re proud of me. But you have to go on journeys, and you have to obey your curiosity, and your need to discover, and need to know.

At one point, I was on Martha’s Vineyard, and I was talking to this younger girl, she was maybe in her twenties, and she was saying, “My father’s a preacher and I’m a lesbian.” And I said, “Look at that world, claim and own that which you can use, and then wave goodbye to the rest of it in the rearview mirror. If you can’t use it, don’t claim it, but don’t let it stop you from becoming the most astonishing version of yourself that you need to become.”

I am, very much so, who I am—I’m very much from Frankfort, Kentucky. But if that shit don’t work, I don’t wear it. Bayard left West Chester, Pennsylvania, was part of this Black community, he protested the segregation of his local movie theatre, and then he came to New York and went on a journey and became who he was. We all go on journeys to complete and explore that which we have not explored.

Was that flight conscious at the time? Or was it that, later on, you thought, Oh wow, I just needed—

No, by six years old, I was going, I’ve got to leave. Then my mother came to New York, to N.Y.U., for some advanced-degree work, when I was twelve or thirteen, and I came with her. And I thought, O.K., got it, this is here, got it, got it. So I can go back home and be horrible and miserable doing high school because I know, later, I’m coming here.

Was that you in high school? Were you just waiting to get out?

No. The school that I went to—it was sort of a Rosenwald, but it was sort of connected to the Black college in town. When I went to this public, predominantly white high school, they decided I was stupid, and they called my mother to talk about putting me in remedial classes—and, even though I didn’t know that at the time, I knew I was being judged. I turned into Eva Perón: “By the time I leave this school, I will be running it!” I was standing on my balcony, saying, “It will be mine!”

I was the editor of the newspaper and the drum major and the editor of the literary magazine and blah-blah—I was already an overachiever, but it magnified. The idea was: I will not be disregarded or dismissed, the community that I come from won’t allow that to happen, the family that I come from won’t allow that to happen, I’m not allowed to be distanced, and you won’t do that. It was a part of the training—first for coming out, then just for arriving in various places and saying, “No, I will not be disregarded. I’ve got work to do, and you being an obstacle to me is inconsequential.” That was part of that training, and it was very specifically community-based training.

What was the locus of community for you, growing up? Was it a church environment?

It was any number of things—the school, the church, the neighborhood. My grandmother lived down the street, and she was a ferocious, protective figure, and very commanding. Frankfort was segregated, and so the idea, therefore, was that you protect the young so that the damage of that structure doesn’t inhibit their possibilities. I still have, to this day, a recording, “Great Moments in Negro History.” All of that was fortification, so that the limitations that were thrust upon us never penetrated past a force field of adults and community and church and relatives, so that you dreamed and you believed and you wanted to achieve, and you felt a responsibility to contribute, and you did all those things, and there was not any equation of racial inferiority at play, at all, ever.

Segregation was over by the time I was growing up, but we still get images put forward as though every Black kid is growing up with a mind infested by racism. It’s, like, No, actually, in my community, the one I grew up in, the moment you do well in school, one time, the whole community is, like, “Please!” Everybody’s trying to lift you up. That attitude shows in the movie—Rustin is drawing on the Quakerism of his youth, he’s drawing on a resource.

Exactly. His mother was a major activist, and very famous Black activists would come and stay with the family. It’s a world of empowerment—it’s a world in which you empower, to the best of your ability, that which is young, so that it can go forward and do things that the previous generation could not do. That’s the responsibility of the community, with that sense of celebration as well as that sense of responsibility. That’s who Bayard was with those kids. He’s saying, “I’m going to challenge you to be smarter, deeper, quicker, better, and you’re going to think about this stuff, and you’re going to do it. And you’re going to work as hard as you possibly can, and nothing is going to stop you, because nothing is going to stop me.”

It’s a celebration of that community, and then reaching out and being as expansive and inclusive as you possibly could be. You wake up one day and you’re going to do an album of Elizabethan songs and Negro spirituals.

A mix that nobody else has achieved.

Go for it! Whatever, if you want to do it, do it. It’s, like, I’m going to Kentucky State, I want to study Kabuki, and so I go and I take Kabuki. Go into the world and be adventurous and be curious, and reach out and connect to as many different people as you possibly can, and build a coalition, and offer yourself up as a warrior to help to make the world more expansive and more inclusive, period. That’s what you do, because it was done for you on a small scale in a little small town in Kentucky.

Then you run the Public Theatre and open up the doors for as many different artists as you possibly can, and feed them and nurture them and give them money, because that was what was done for you. Anytime you come into contact with an obstacle, figure out how that obstacle is not going to stop you. That sense of that responsibility, I really recognize in Bayard, and that sense of the community, and that sense of the hard work. I use the word “defiance,” but defiance almost is giving too much credit to the obstacle. He comes into contact with Adam Clayton Powell, who’s out to shame him, and then he puts on a display of how brilliant these kids are and what they’ve achieved.

Also, the story of Pasadena: more people knew about it than is revealed in the movie, but I wanted to have that as a little secret corner of shame, so that, as the movie is building toward the march, the movie is building to him exposing that last little corner of shame, so that, just before he goes to D.C., it’s him exorcizing that from his system. Going to D.C. isn’t just for the march—it’s claiming the streets of a segregated town, which is what D.C. was at the time, and claiming the sunlight and the daylight as your own, so that the first time you’re kissing that boy, it’s not in some dark alley with fire escapes hovering over you. He’s on a journey of liberation.

You mentioned your tenure at the Public Theatre. One of the great struggles and triumphs of your tenure there was making it a place where more people could come. It seems now that the struggle for big nonprofit theatres is just to keep existing. You’re still a participant in the theatre, if not at the same intensity as you once were. What is your view about what’s happening now, and how it relates to some of the challenges you faced?

I think any time you come into contact with a complication—as I was talking earlier about my health—it’s frightening and overwhelming, but it’s also a chance to reinvest, rediscover, and rebuild. I don’t feel equipped to offer forth a solution, but it’s a really interesting time that all these regional theatres, post-COVID, are going through. It’s post-COVID and post-George Floyd, so people are saying, “Let’s engage people of color in leadership positions,” in a way that has never been done before. I think I was one of two, maybe three, people of color who were leading an arts organization at the time when I was at the Public, so it’s a really interesting time, trying to commit and do the right thing in a landscape that is radically shifting, in a landscape where the subscriber base is virtually vanishing. How do you do that? Do you try to bring some commercial stuff to Broadway so you can get that money? How do you hold on to the passion of the vision in that landscape?

I’m not sure, I’m not going to bring up any solutions, but it really is fascinating, and smart people are involved in trying to solve it.

Thinking about the deep tectonics of the theatre, one could ask a similar thing about the business of movies—your actors can’t even talk about this movie yet, on account of the strike. Have you learned anything about the movie business in this moment? The Directors Guild, obviously, was able to patch things up quickly.

Yeah, and I’m in the Writers Guild as well. I’ve been working—literally, it’s, like, I was editing and then added the in-credit songs, and, after that, I just started going around talking to lovely people like you. I’ve just been doing that fucking non-stop, you know what I mean?

I’ve got one last question for you, and this one’s for me, because I love Chris Rock, who plays Roy Wilkins. It’s such unexpected casting. How did that come to be?

It was that two things happened. Chris reached out to me and said, “You’re doing a new movie? I would love to work with you.” And then I was looking at pictures of Roy Wilkins, and I thought, He kind of looks like Chris Rock. It was the same with Audra [McDonald]. I went, Oh, Ella Baker. Audra has this extraordinary purity of focus. But Chris reached out, and then I was looking at pictures of Wilkins, and it was literally that: Wow, O.K., that would be interesting. And then you go on the journey. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com