Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

The New York Film Festival begins Friday. As I noted last year, the festival’s main slate is increasingly given over to movies by major Hollywood figures. (This year’s opening night brings Todd Haynes’s “May December,” starring Natalie Portman and Julianne Moore.) So, for now, I’ll concentrate on films by independent and international filmmakers who don’t yet have instant name recognition for most viewers but whose work deserves (and needs) the serious attention that a festival showcase brings. (One of the best films on display, “All Dirt Roads Taste of Salt,” the first feature by Raven Jackson, premièred at Sundance this year; I wrote about it then and will reënthuse about it closer to its November 3rd theatrical release.)

Ryûsuke Hamaguchi’s latest film, “Evil Does Not Exist” (Oct. 5, Oct. 7, and Oct. 11), is both a great film in itself and a retrospective illumination of the filmmaker’s previous masterworks—“Happy Hour,” from 2015, and “Drive My Car,” which won the Oscar for Best International Feature in 2022. In the new film, Hamaguchi boldly stands cinematic dramaturgy on its head, starting the film with an extended sequence of images that don’t tell much of a story and keep the audience guessing. The opening scene occurs in a snowy forest, where the camera seems to plunge from treetops toward the ground. Yet it gradually becomes clear that the forest is being viewed from the ground—the camera looks upward fixedly while in relentless forward motion, in a way that no walker ever could. There is a walker, though: a girl is making her way through the woods, eventually accompanied by the sound of a power saw. The scene that follows could be considered absolutely pointless or absolutely sublime, a dichotomy that turns out to be at the moral core of the movie. A man with a power saw is cutting long logs into shorter pieces. Then he stands each piece on its end, atop the smoothed surface of a wide tree stump, splits it with an ax, and moves on to the next piece. This is all in one long take, at the end of which the man has a neat pile of firewood. He steps back, lights a cigarette, and takes a contemplative break.

Were the movie made up entirely of sequences like this, I’d have been in a cinematic heaven of poised, documentary-like observation. But there is a story—albeit one that Hamaguchi unfolds gradually in further sequences of intent observation—and the story makes such observation its very point. The man is joined by another one, and they fill plastic tanks with water from a gentle stream nearby and pack the tanks in a car. Health officials or scientists taking samples? No: the woodsman, Takumi (Hitoshi Omika, a first-time actor who has previously been an assistant director to Hamaguchi), is helping gather water for making the noodles served in a restaurant that the other man and the other man’s wife run. (Takumi also offers the restaurant leaves of wild wasabi, a local specialty, that he has foraged—a brief scene that delivers yet another form of aesthetic enticement to go with the film’s visual ones.) After the water delivery, Takumi drives to a nearby school to pick up his young daughter, Hana (Ryo Nishikawa), but she has already left. Catching up with her, he takes her on a long walk through the woods, pointing things out and sharing his knowledge of plants and animals. Eventually, Hamaguchi, having patiently built up this intricate and deeply rooted evocation of rural life, introduces an element that threatens its very existence—the arrival of two representatives of a businessman who plans to open a glamping resort in the region.

Hamaguchi, who also wrote the script, conceived the film with Eiko Ishibashi, the composer of the score for “Drive My Car,” who lives near the village where the movie takes place. As in Hamaguchi’s previous masterworks, the drama is concentrated in dialogue. Watching his elaborate and nuanced depiction of a long village meeting where residents, including Takumi and the family of restaurateurs, confront the representatives, I felt as if the scene could have been taken from a documentary by Frederick Wiseman, whose analyses of institutions and communities often emerge by way of such extensive displays of democratic debate. But there’s a subtle difference between the dialogue here and that of Hamaguchi’s other films: usually, the dialogue sparks drama; here, it crystallizes a drama latent in the documentary elements that underpin the movie. Elaborate dialogic scenes—one of the most memorable, filmed mainly in one long, tense take, listens in on the two representatives having a wide-ranging confessional discussion in their car—glow with a spiritual aura that reflects both the countryside’s natural splendors and Takumi’s own quasi-mystical authority. The inherent opposition of the aesthetic realm—whether visual beauty or nobility of character—to a modernizing drive for utility and practicality, for industrial development and professional status, defines the very stakes of the plot.

In “Evil Does Not Exist,” Hamaguchi’s dramatic construction and visual style are even more daring and distinctive than in his previous films, but, this time, he can’t quite stick the landing. No spoilers, but the ending, which is both vague and abrupt, suggests a problem of scope. “Happy Hour” runs five hours, “Drive My Car” nearly three, and their length is in natural accord with the gradual pace of their dialectical complexities; by contrast, “Evil Does Not Exist,” runs only a hundred and six minutes, and this relative brevity feels like an artificial truncation. The ending masks a missing—or unimagined—additional hour that would follow the film’s plethora of closely observed details to their logical outcomes. Yet it almost doesn’t matter; the gratifications that lead to the rapid wrap-up are so distinctive and intense that they could nearly win the movie the unusual status of an unfinished masterpiece.

Photograph courtesy The Cinema Guild

A bold approach to the relationship between images and dialogue is also a mark of “In Water” (Oct. 1 and Oct. 2), a sharply original movie by the hugely prolific South Korean filmmaker Hong Sangsoo. (It’s one of two new works he has brought to the festival.) As with much of Hong’s work, “In Water” revolves around Seoul’s film industry and its independent peripheries, and its protagonist, a young director and actor named Seoung-mo (Shin Seok-ho), faces crises that reflect the demands of Hong’s own practice. Seoung-mo pays out of his own pocket for a weeklong stay—with an actress (Kim Seung-yun) and a former director (Ha Seong-guk)—at a small seaside town, aiming to make (and star in) an entire short film during the week. He arrives with a general idea for a story about an actress but loses confidence in it. As the trio wanders on a rocky beach, he watches a woman picking up garbage left by tourists and cooks up a scenario to be improvised around the idea of this person. There’s some personal backstory between Seoung-mo and the two other participants, and he also has a romantic drama taking place on the side—all of which adds layers of emotion not only to the characters’ meandering discussions about frustrated ambition but even to seemingly simple decisions about food and lodging. As in most of Hong’s films, much of the dialogue unfolds in long, static takes that are nonetheless so sharply composed and so sensitively performed that they buzz with life and drama. But Hong also adds a droll and daring twist, making many of the images mildly out of focus, blurring detail but not obscuring figures. This has the odd effect of making the dialogue stand out even more, as if it were inscribed on the screen. Using this trope to heighten the emotional impact of the characters’ conversations, Hong delivers a daringly conceived film with a passionately moving ending, in which the young filmmaker’s artistic and personal troubles mesh with cinematic form to reach a sort of grimly ambiguous exaltation.

Photograph by Barton Cortright / Courtesy Magnolia Pictures

For Hong’s protagonist, acting in his own picture is a form of self-analysis, and the same is true for the Brooklyn-based writer and director Joanna Arnow, who plays the lead in her melancholy comedy “The Feeling That the Time for Doing Something Has Passed” (Oct. 5 and Oct. 7). She plays Ann, a thirtysomething woman who works in a vaguely educational, vaguely technological, ultra-bureaucratic corporate setting. She’s in a tensely loving but smothering relationship with her parents (played by Arnow’s own parents), old-school lefties who are sometimes earnestly and sometimes obliviously hypercritical. She’s also in a sexual relationship chillingly devoid of romance with a man named Allen (Scott Cohen), by whom she seeks to be dominated and humiliated. The center of the movie is Ann’s quest for a romantic relationship of mutual regard that can also provide the sexual pleasure she derives from submission. Along the way, Ann is at times underdominated and at times overdominated (as by one man who gags her and dresses her as his so-called “fuck pig”); her job is unsatisfying, her friends are not understanding, and none of the sectors of her life overlap. Arnow writes Ann and the other characters as frank yet cagy, verbally adroit yet terse—both evasive in their confessions and confessional in their evasions. The performances, too, display inhibited candor that yields involuntary expressivity, and Arnow (who is also a cinematographer, though not for this film) matches these with subtly confrontational compositions; Ann is often naked, and Arnow’s images depict the character’s vulnerability and even humiliation frankly but plainly, without adding to them—and without sharing the dominant perspective of Ann’s so-called masters. The movie’s scenes, often snippet-like blackout sketches, distill pain and ardor into catch-them-quickly bubbles. The result is an idiosyncratic and poignant film that offers evidence that a state of grace may be far from graceful.

Photograph courtesy Kino Lorber

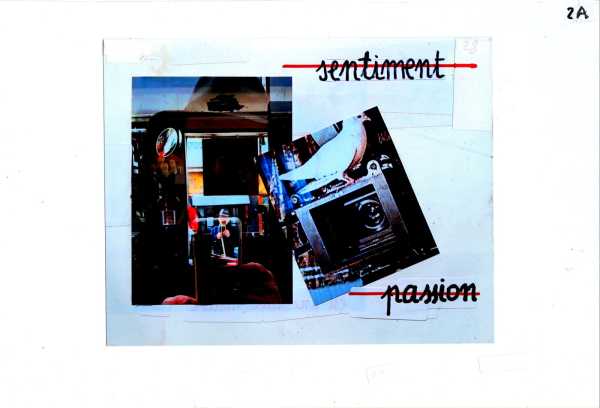

Jean-Luc Godard died in September, 2022, at the age of ninety-one. In his last years, he was working on an adaptation of the 1937 novel “False Passports,” by the French writer Charles Plisnier, and conveyed his work materials—storyboard-like collages, a bit of live-action footage, and audio clips—to his assistant, Fabrice Aragno, with explicit instructions for their editing. The result is the nineteen-minute film “Trailer of a Film that Will Never Exist: Phony Wars” (Oct. 2-4), which plays like a distillation and an elucidation of Godard’s last decades of work. In the novel, as Godard says in voice-over, Plisnier, a Trotskyist expelled from the Communist Party, “paints a portrait, imaginary or real, of a few contemporary activists whom he’d known around 1920.” Godard mentions that the novel makes him want to combine his own recent, fragmented style with something more classical, along the lines of Jean-Pierre Melville’s first feature, “The Silence of the Sea” (1949), a drama of the interactions between a family in rural France and a Nazi German officer who’s billeted with them. But the film he delivers is more allusive and speculative—a visual and sonic collage that outlines wide-ranging historical musings. There are images and snippets of text (a color picture of a young woman pasted onto a photocopy of a paragraph of Plisnier’s book, black-and-white photographs of characters seemingly from a century ago) alongside music and sound clips from some of Godard’s later films (including “Our Music” and “Film Socialism”). References include internecine conflicts on the left, especially during the Spanish Civil War; France’s actions in the Algerian War and the resulting antiwar campaign among French leftists; the Second World War and the Holocaust; Hannah Arendt and Palestine; the Bosnian War and Russia’s ongoing attack on Ukraine. Godard, in his later years, became obsessed with history. He was not quite a conspiracy theorist, but he was certainly a theorist of conspiracies, seeing subterranean patterns and connections that also threaded through the history of cinema itself and thus proved immensely productive of cinematic visions. An onscreen text in the new film, a quote from Wisława Szymborska, reads, “The most ephemeral of moments possesses an illustrious past”; Godard's later work thus explored, as if archeologically, the mighty image-repertory of the social and artistic past lurking within the moments that he filmed. This “trailer” reflects both his powerful reprocessing of extant images (including his own) to unite the archive and personal memory—and his still-raging desire to create a new classical cinema in his own image. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com