Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

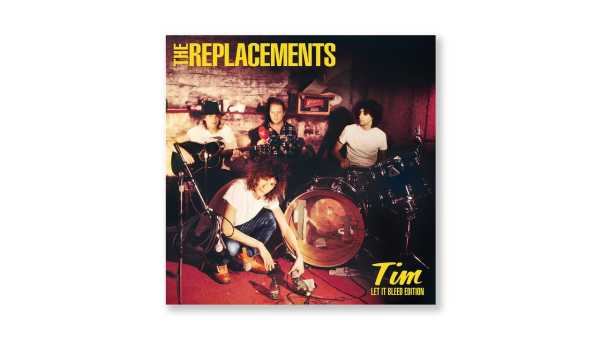

The year was 1985, Ronald Reagan’s Morning in America was in full swing, and the Minneapolis-based Replacements were making moves. Following a string of critically beloved and commercially overlooked releases on the tiny local indie label Twin/Tone, the band members were preparing their first LP for the Warner Bros.-backed major label Sire Records. Their songs were ecstatic, romantic, literary, and heartbreaking. Their brand was chaos: live shows that were transcendent or tragicomic depending on the drugs involved; albums that interpolated brilliant Stones-adjacent youth anthems and devastating country weepers with slapdash Kiss covers and improvised jams where no one played their actual instrument. Some wag once termed the Replacements “The little engine that could but didn’t fuckin’ feel like it.” But the band cared too much, and now the industry they collectively both mistrusted and fetishized was knocking at the door, proffering an opportunity. The resulting LP was “Tim,” which has been given the deluxe-reissue treatment, in the form of a five-disk set called “Tim: Let It Bleed Edition.” Some forty years later, the album feels like a five-alarm blaze, prophesying an era of corporate-driven consensus and the outsourcing of America’s manufacturing sector.

The Replacements’ studied unprofessionalism had always been a point of pride, and possibly an aesthetic hedge. In a time of carefully crafted consumer products, here was a band so aggressively untamable that no one could ever accuse the group of selling out. In a world full of glossy fakery, its self-vandalizing, clown-school bloodletting was the genuine article. Or at least something genuine. And yet, unlike more avant-garde-influenced peers such as Black Flag and Sonic Youth, the Replacements made music that was a populist offshoot of influences like Rod Stewart and Marc Bolan, swaggering performers who had ridden meat-and-potatoes rock to global fame. However attitudinal the Replacements might have presented themselves, it didn’t take a great deal of squinting to see the possibility of the band as arena fillers. The lead singer and songwriter Paul Westerberg was a punk-rock Jackson Browne, a pugilistic but ultimately heartsick poet with matinee-idol looks. The bassist, Tommy Stinson—thirteen when he joined the band, all of eighteen when “Tim” was tracked—appeared to be assembled in a rock-star factory, with the lank frame and chiselled beauty of a spare member of Duran Duran. Warner Bros. didn’t sign the Replacements because the members oozed cachet. The company signed them because it saw dollar signs.

Thus “Tim” commences with a binary choice. The opening track is called “Hold My Life,” and the decision is between fame—or at least a life-changing increase in notoriety—and something like a tactical retreat from the limelight. “Time for decision to be made,” Westerberg intones hoarsely over a driving pre-chorus: “Crack up in the sun / Or lose it in the shade.” A sentiment worthy of Jay Gatsby himself. By the end, the Replacements did a little bit of both.

“Tim” is a great group of songs, possibly the best set that Westerberg has ever strung together for a single LP, but the revelation now is how powerfully the album captures the spiralling class anxieties of the era. As a hardscrabble collection of high-school dropouts and juvenile delinquents, the Replacements’ four members came by their umbrage and fatalism organically. “Jail, death, or janitor,” was Westerberg’s diagnosis for the range of plausible outcomes for the band members, and, indeed, in the group’s early days, he served as a janitor in the Minnesota senator David Durenberger’s office, an interloping pawn in the corridors of power. Class consciousness always figured into the Replacements’ catalogue— including the looking-down-the-nose partygoers of “Color Me Impressed” and the golf-obsessed surgeon concerned with making his tee time on “Tommy Gets His Tonsils Out”—but on “Tim” that rage and resignation deepens. Likely because Westerberg has always nervously eschewed the significant political content of his own work, the press and biographers have been slow to characterize “Tim” as what it truly is: a great working-class treatise whose thematic and musical DNA runs through the Stones’ “Beggars Banquet” and Bruce Springsteen’s “Darkness on the Edge of Town.”

Take, for instance, the joyously buoyant third track, “Kiss Me on the Bus,” an amorous flirtation and an echo of the Stones’ “Factory Girl” that depicts two paramours who will need to make their emotional intentions clear within the insoluble strictures of public transportation. “Hurry, hurry!” Westerberg implores, while looking for a kiss. “Here comes my stop!” Or its transport-centric companion piece “Waitress in the Sky,” which on its surface is a mean-spirited broadside against flight attendants but was actually a blow-for-blow description of the kind of abuse that Westerberg’s sister Julie experienced as a flight attendant. “A real union flight attendant, my oh my,” goes the sneering chorus. “You ain’t nothing but a waitress in the sky.” The invocation of union allegiance as a source of ridicule is not coincidental. In 1981, Reagan had christened an era of scorched-earth anti-union policy by firing en masse the striking air-traffic-controllers’ union PATCO. As safety nets for the working class and working poor were dismantled throughout the eighties and nineties, a fashionable stance among the emergent class of Milton Friedman- and Ayn Rand-informed right-wingers was that labor organization was a hubristic overreach at best and a Communist plot at worst.

On the enduring deep cut “Swingin Party,” a ballad partially about being economically outgunned in every social circumstance, and partially about the futile exertions of the under-credentialled, looking for work is presented as a zero-sum choice between abject poverty and a life of stultifying dullness: “Pound the prairie pavement / Losing proposition / Quittin’ school and going to work / And never going fishing.” On the track “Little Mascara,” Westerberg demonstrates a trait that was glancingly rare among male songwriters of his era, the ability to write credibly about women. The story of a struggling young mother trapped in a loveless marriage and still dreaming of some way out, “Little Mascara” evokes Tennessee Williams in its depiction of a gifted individual circumscribed by their social context. When he sings “For the moon / You keep shootin’ / Throw your rope up in the air / For the kid you stay together / You nap him and you slap him in a highchair,” the sublimated implications of multigenerational trauma are made explicit. On some level, and to varying degrees, all of the members of the Replacements had been born into a cycle of abuse, addiction, or depression. In “Little Mascara,” you wish the best for the mother, but your heart breaks for the baby. Fear and sadness will be the psychological foundation on which they’ll have to build a life.

Loudest of all, there’s “Bastards of Young.” A generational howl of fury that commences with a literal scream. Here is the unvarnished offspring responding to a boomer generation that, having first controlled the cultural narrative, increasingly controls the political one. “God what a mess / On the ladder of success,” Westerberg contemptuously sings, taking sport at the rapidly receding myth of American upward mobility. “You take one step / And miss the whole first rung.” Like Randy Newman’s “Louisiana 1927,” it is a perfect American song, capturing a time, place, and energy that resonates and reoccurs throughout history.

To the band members’ frustration, and also possibly their relief, “Tim” did not prove the kind of commercial breakthrough that would soon be achieved by R.E.M. The album’s famous, strangely echoey production by the former Ramone Tommy Erdelyi was neither particularly radio-friendly nor organically punk-adjacent, and confused just about everyone. The front cover looked a little bit like L. Ron Hubbard’s “Dianetics.” In a legendary bit of reckless self-sabotage, the band was so drunk and powerfully loud on a “Saturday Night Live” appearance that it remains unclear to this day whether the performance represented a shameful low or a resounding victory. “Tim” peaked at No. 183 on the charts, there being something faintly comical about even bothering to enter the Billboard 200 at such a vaguely insulting level.

And yet, on the occasion of the expansive new reissue, the cultural relevance of “Tim” is at an all-time high. “Bastards of Young” has become a calling card of sorts for misfit stories with a socioeconomic subtext, having been featured in Season 2 of the FX restaurant drama “The Bear.” The new box set is preoccupied with fixing perceived mistakes: a new mix, a new remaster, a counterfactual history of an awkwardly perfect album. There’s lots of fun stuff on the updated version well worth hearing—scrappy tracks from a demo session with the band’s spiritual mentor Alex Chilton, a typically wobbling and bracing 1986 live set from Chicago—but the perverse net effect is of taking a defensive stance to an LP that never truly needed defending. The new Ed Stasium remix is fine, but it was never really Erdelyi’s heavy hand that prevented “Tim” from attaining its commercial aims. The original mix sounds no more gated or dated than “Born in the U.S.A.,” which never had any difficulty connecting to a mass audience. In the 2003 documentary “Come Feel Me Tremble,” Westerberg is asked his opinion of “Tim” and offers a typically gnomic and incisive verdict: “Coulda been.” Whether he is invoking Marlon Brando’s “coulda been a contender” monologue from Elia Kazan’s social-realist masterpiece “On the Waterfront” intentionally or just by osmosis doesn’t really matter.

After “Tim” was released, the members of the Replacements descended into interpersonal drama even more extreme than their accustomed standards. The guitarist Bob Stinson—Tommy’s older brother—was dismissed for reasons of excess consumption and increasingly erratic behavior, which is a bit like censoring a sheep for being part of the herd. The longtime manager Peter Jesperson was jettisoned for thinking too small or thinking too big or maybe some combination of both. Remarkable music followed from there. “Pleased to Meet Me,” from 1987, a masterpiece recorded at Ardent Studios with the Memphis legend Jim Dickinson, further sharpened the band’s sonics, centering Westerberg on guitar. “Don’t Tell a Soul,” released in 1989, was the band’s last big swing and featured its most commercial sound ever, a handful of good songs, and the closest thing the unit ever had to an actual hit, the keening “I’ll Be You,” which peaked at No. 51. “I’ll Be You” referenced the group’s travails with typical self-deprecation. “A dream / too tired to come true / Left a rebel without a clue.” An opening tour for Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers exposed them to a huge new audience, and it did not go well. Once it became clear that the Petty crowd was disinterested in both its music and its antics, the Replacements played worse and worse every night and tried to quit the tour, only for Petty himself to insist that the members honor their contracts. Petty later borrowed Westerberg’s “rebel without a clue” formulation for “Into the Great Wide Open,” a tune about a talented but vain and erratic songwriter maladroitly navigating the music business. It became a smash.

The Replacements—or at least Paul and Tommy backed by other musicians—staged a successful series of reunion dates between 2013 and 2015 where they were received by ecstatic festival crowds, singing along with every word. This seemed to spook the notoriously skittish Westerberg, who is a bit of a hermit, like his hero Ray Davies, back into hiding. Chris Mars, now a visual artist, prefers to keep his distance from his old mates. Bob Stinson died of organ failure in 1995, at the age of thirty-five. Tommy Stinson turned out to be the true lifer, doing time in Guns N’ Roses and animating his own version of the Replacements’ underdog ethos as front man of the roots-rock band Bash & Pop. Having started working as a literal child, he never stopped.

“Tim” ends fittingly with the ritualistic holding pattern “Here Comes a Regular.” It’s a barroom ballad that would fit as easily on Frank Sinatra’s “In the Wee Small Hours” as it would on Merle Haggard’s “Serving 190 Proof.” The song is distinguished by its epochal opening couplet: “A person can work up a mean, mean thirst / After a hard day of nothing much at all.” A final last call from a freighted time when both a band and a nation hung in the balance. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com