Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

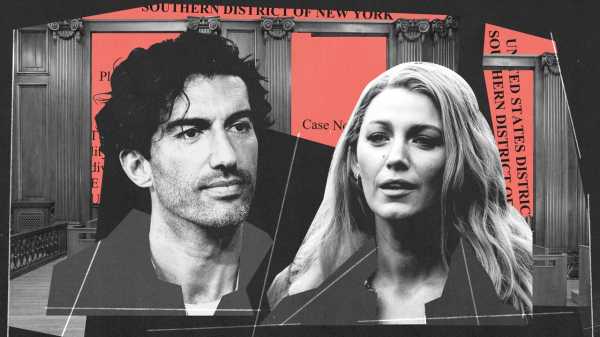

In the faux aristocracy that is Hollywood, a Blake Lively should not have reason to meaningfully cross paths with a Justin Baldoni. Lively, best known for playing Serena van der Woodsen in the CW series “Gossip Girl,” is an ingénue of teen-soap television, who has parlayed a career as a film actor into a permanent role as a domestic diva slash style icon. In 2022, she co-chaired the Met Gala; two years later, she appeared on the cover of Vogue’s September issue. She is married to Ryan Reynolds. She is friends with Taylor Swift. She is famous.

Justin Baldoni is an actor who did not exactly soar after a long turn on “Jane the Virgin,” a show that aired on the same network as “Gossip Girl.” Over the years, he has become, if not famous, then at least recognizable, mostly for his activism, which is of the male-feminist strain. He has released a podcast and books—for both adults and children—about modern masculinity. In 2019, Baldoni, having made the leap from actor to director, acquired the rights to “It Ends with Us,” a book by the majorly popular romance novelist Colleen Hoover. At that point, the book, billed on Hoover’s Web site as “an unforgettable tale of love that comes at the ultimate price,” had already sold well. But then, in 2022, it exploded on BookTok, an event that spurred the purchase of millions of additional copies. Baldoni, a self-serious man, has spoken about his acquisition luck as “providence.” No surprise, considering this self-seriousness, that Baldoni was drawn to Hoover’s novel in the first place. Lily Bloom, the protagonist, is sorting out her complicated relationship to her recently deceased abusive father when Ryle Kincaid, a handsome neurosurgeon, comes into her orbit. One daddy gone, another come—Hoover makes a fable about the private and cyclical dangers of a certain kind of New England family. The project would be co-produced by Wayfarer, Baldoni’s production company, and Sony, which would distribute the film. Casting of the two lead characters was announced in January of 2023. Lively would play Lily. Baldoni would both direct the film and play the character of Ryle.

The movie, which premièred in August of 2024, was a box-office success. It is mediocre but watchable. Lively’s Lily Bloom is a cipher for the millennial woman resisting the pull of becoming her boomer mother. She wants to run a business—a flower shop, but, don’t worry, she, too, groans at the pun in her name. Baldoni’s Ryle Kincaid, meanwhile, is unnerving. Not because he is the sexy bad boy, luring us in with his beard and his six-pack abs, before he makes his predictable and volatile turn. He is unnerving because he is vacant, inert. He exists only to be set off. That’s when he’s alive.

Last year was the year of the overbearing promotional tour—“Wicked,” “A Complete Unknown,” “Challengers.” But something was not right during the tour for “It Ends with Us.” For one, Baldoni and Lively were virtually never seen together. They stayed away from each other on the red carpet; they sat in different theatres for the première. On Instagram, fans noticed that, at some point, Lively, Reynolds, and Hoover had unfollowed Baldoni, though he still followed them. Clearly, something had happened on set, and signs pointed toward most of the cast being Team Lively. (Many of them had unfollowed Baldoni on Instagram, too.) But was it because Lively was in the right, or was it because she was simply the more powerful industry figure—the person the rest of the cast could not afford to piss off?

As fans watched videos of Lively promoting “It Ends with Us,” public opinion began to shift. The interviews were jocular, an approach that seemed tactless, given the film’s subject matter. The promotional tour coincided with the launch of a new hair-care line from Lively, Blake Brown, and she also used the film to promote the beverage company she founded back in 2021, Betty Buzz, releasing a list of cocktails inspired by the movie (e.g., “Ryle You Wait”). She conspicuously avoided making any mention of domestic violence. “Grab your friends, wear your florals, and head out to see it,” she said, in a video posted to Instagram in August, wearing her own yellow floral number. “Wear your florals? WTF? This isn’t another Barbie movie type film,” one user wrote, in a comment with more than eleven thousand likes. “So damn tone deaf. This is why we need Justin to do the marketing.”

Baldoni, in his appearances, spoke sombrely, always billing the movie as a message film. Here was an earnest man who wanted to protect the solemnity of the subject, fans felt. The drama heightened when Lively casually told a reporter, on the red carpet, that Reynolds had written a key scene in the movie—something that, “Entertainment Tonight” confirmed, had happened without the knowledge of Baldoni or the screenwriter. There were other reports that Lively, unhappy with the initial cut of the film, had commissioned a separate cut from Shane Reid, the editor of “Deadpool & Wolverine,” a movie starring Lively’s husband. A new narrative quickly took shape: Baldoni had been muscled out of the creative process for his own movie. When asked, on the red carpet, if he planned to direct the film’s sequel, Baldoni demurred. “I think there are better people for that one,” he said. “I think Blake Lively’s ready to direct.”

It was a bad look for Lively and Reynolds, to be sure. And yet it didn’t fully account for the sheer amount of hatred directed toward them online. As a user tweeted in August, “Watching women go full qanon to make blake lively seem like a cartoon villain who conspired with her evil husband to steal poor sweet male feminist justin baldoni’s movie from him when all he wanted to do was advocate for abused women . . . bonkers . . .”

In late December, Megan Twohey, Mike McIntire, and Julie Tate published an article in the Times titled “ ‘We Can Bury Anyone’: Inside a Hollywood Smear Machine.” According to the story, as production on “It Ends with Us” was set to resume following a pause for the 2023 writers’ strike, Lively called a meeting with Baldoni, Jamey Heath—the lead producer for the film—and other producers. She spoke of abuses she had allegedly experienced on the set: Baldoni and Heath had entered her dressing room while she was breast-feeding; Heath had shown her a video of his naked wife. According to a complaint letter Lively filed at the time of the article’s publication, she presented a list of thirty requests that she wanted the team to agree to before she returned to work. They ranged from basic safeguards (“An intimacy coordinator must be present at all times when BL is on set in scenes with Mr Baldoni”; “If BL and/or her infant is exposed to COVID again, BL must be provided with immediate notice . . . without her needing to uncover days later herself”) to protection from more bizarre acts (“No more mention by Mr Baldoni of him ‘speaking to’ BL’s dead father”; “No more private, multi hour meetings in BL’s trailer, with Mr Baldoni crying, with no outside BL appointed representative to monitor”). The Times report then goes on to present an intricate media campaign, conducted by Melissa Nathan, a crisis-P.R. executive retained by Baldoni and Heath, who is best known for representing Johnny Depp during his trial with Amber Heard. The campaign, as described by the Times, involved the use of social media and the cultivation of gossip-rag writers, to preëmptively “cancel” Lively in retaliation for her earlier accusations. (An attorney for Wayfarer said in a statement to the Times that the studio, its executives, and its public-relations representatives “did nothing proactive nor retaliated” against Lively.) For months, the report states, Nathan and her team planted anti-Lively sentiment across all manner of media. They tracked the development of the narrative: the sensitive, male underdog, and the greedy diva. There’s discussion of the best promotion strategy for “It Ends with Us”; although Sony had advised that the actors stick to a more cheerful marketing plan for the movie, Baldoni had decided to shift his rhetoric to focus on survivors of domestic abuse—an intentional sympathy ploy, according to Lively’s complaint letter. The article presents celebratory text messages between Nathan’s team, Baldoni, and his publicist, Jennifer Abel, taken from Lively’s complaint letter: “Narrative is CRAZY good,” Nathan writes, in reference to the boom of online sympathy for Baldoni, and dislike for Lively. Lively’s complaint letter, which she filed with the California Civil Rights Department, alleged sexual harassment by Baldoni, Heath, Wayfarer, the public-relations executives, and an independent digital strategist who was allegedly hired to push online hate against Lively; more than a week later, she filed a lawsuit in New York.

Rarely is the business of celebrity public relations so exposed. “These claims are completely false, outrageous and intentionally salacious with an intent to publicly hurt and rehash a narrative in the media,” Baldoni’s lawyer, Bryan Freedman, wrote, in response to Lively’s allegations. And yet the response from the industry was swift. W.M.E., the talent agency representing Baldoni, dropped him as a client almost immediately after the article’s publication. Sony also quickly indicated that it supported Lively, as did her co-star, Jenny Slate, and other celebrities, including Amber Heard. But an atmosphere of solidarity did not really build around Lively online. Why not? Baldoni’s minions may have smeared her—to what extent, we don’t yet know—but Lively was already vulnerable. She is a prime target for roving white-girl-hate. She is a broad—sarcastic, charming, abrasive. She does not always play along with journalists during junkets. (During the tour for “It Ends with Us,” the entertainment journalist Kjersti Flaa circulated an old interview with Lively, and claimed that Lively had made her want to quit her job.) Lively and Reynolds have long been an It Couple. But their likability has taken some hits over the years. In 2012, the two got married on a plantation in South Carolina, for which Reynolds later apologized. (“It’s something we’ll always be deeply and unreservedly sorry for,” he told Fast Company in 2020. “It’s impossible to reconcile.”) Lively’s close friendship with Swift hurts her, too, in the wars of reputation. Swift is enormously powerful. Fair criticism of Swift’s economic and cultural powers curdles easily into misogyny. These are women whom other women can allow themselves to hate.

And then there’s the matter of the Times article. Twohey is known, alongside Jodi Kantor, as a key architect of the contemporary #MeToo narrative. In 2018, they won a Pulitzer, alongside The New Yorker’s Ronan Farrow, for their reportage on Harvey Weinstein’s career of abuse and violence. It was the beginning of a movement, fuelled by women’s speech—confession mitigated through the media institution. Up until then, the narrative of the victim of sexual assault or harassment had been “recognized” only as a legal narrative or a memoir narrative, truthtelling sequestered to the purview of the criminal courts or the book. This Weinstein reportage legitimatized, in the cultural field, the atmosphere surrounding the violence. Their reporting not only unveiled the truth but unearthed a personal narrative. Lively’s allegations, as detailed in the Times’ recent investigation, lacked this aspect. She did not sit for an on-the-record interview. The article did not run with her portrait. She lacks the victim pedigree, the personal exposure, that the people want.

Baldoni has sued the Times for libel and fraud. He seeks damages of two hundred and fifty million dollars. (His lawyer has indicated that he intends to sue Lively later.) In Baldoni’s eighty-seven-page lawsuit against the newspaper, his legal team claims that “Lively found willing allies at the New York Times,” accusing the reporters of removing critical context in their reproduction of text-message exchanges from the Baldoni P.R. team: “When read in full, the exchange reveals Nathan and Abel engaging in facetious, juvenile banter—not conspiring against Lively.” The language is canny. According to the suit, the Times omitted an upside-down smiley-face emoji from one of Abel’s texts—part of a larger attempt, the suit claims—to misrepresent a sarcastic text as a serious one. (“Our story was meticulously and responsibly reported,” a Times spokesperson said in a statement issued to CNN. “It was based on a review of thousands of pages of original documents, including the text message and emails that we quote accurately and at length in the article.”) Baldoni’s legal team has also produced a text message from Lively, allegedly indicating that she once invited Baldoni into her dressing room while she was pumping breast milk. The Baldoni team is heightening a sense of conspiracy around the situation, during a period in which trust in mainstream organizations like the Times has eroded. Meanwhile, watchers on social media flip between Team Lively and Team Baldoni. Lively had been seen as an élite, too big to enter the state of victimhood. Baldoni looked like the victim; he had aligned himself with victimhood. After the Times article, public opinion began to shift toward Lively, with some pop-culture critics going as far as to issue apologies to her. But now Baldoni’s countersuit has shifted the tide again, introducing confusion and unease. On January 8th, Baldoni’s lawyer, Bryan Freedman, a character in his own right, went on Megyn Kelly’s podcast to share a voice note from Baldoni. (Freedman also represents Kelly.) In it, Baldoni describes being mistreated at the première of “It Ends with Us.” Baldoni’s suit claims that Lively attempted to block him and his group from attending the première, sending them “to the basement” instead. The night, he says, was supposed to be “so materialistically joyful.”

We are no longer in the #MeToo era. The standard of “believing women” did not really become a standard. Stories of harassment and abuse now receive a curdled, cynical, and exhausted reception. A crop of disaster public-relations experts prosper in this new environment, as do self-appointed “legal experts” on TikTok and other social-media commentators. And so Lively’s allegations against Baldoni were never going to be seen as brave, but, rather, as the kindling for a culture war. The late twenty-tens genre of #MeToo reportage cannot thrive on today’s volatile Internet. Information is misinformation and vice versa. Victims are offenders and offenders are victims. The word that comes up again and again in all the Internet litigation of Lively v. Baldoni is “narrative.” Abuse seems to be far from anyone’s mind. What matters is which side’s story is better suited to the politics of our time. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com