Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

At some point in the past decade or two, dance-music d.j.s discovered a way of punctuating their sets with a prank. Just as the music was reaching a crescendo, it would glitch, then cut out completely; videos playing above and around the stage would be replaced by the “blue screen of death,” from Microsoft Windows. The system had crashed! An awkward silence would descend as error messages popped up, accompanied by the familiar Windows alert sound. But then the alert sounds would fall into a rhythm, forming the backbone of a new song. When the beat dropped on the new track—there were many different versions of the “Windows Remix”—the crowd would go nuts.

If only it were that easy, in real life, to find out whether a system has failed. More often, we’re left to argue about it. After Luigi Mangione allegedly killed Brian Thompson, the C.E.O. of UnitedHealthcare—Mangione has pleaded not guilty—the fact that large numbers of Americans approved of the murder seemed, to some, like proof that the health-insurance system had failed. Describing the sharp rise in felony assaults by repeat offenders in New York City, Jessica Tisch, the police commissioner, blamed “a broken system, one that doesn’t put the rights and needs of victims first.” The long-tolerated crimes of Jeffrey Epstein suggest a rotten system; the fact that Donald Trump could run for President even after inciting the January 6th riot shows, to many, that our system of checks and balances has failed. It’s trivially easy for most people to name a slew of broken systems, financial, technological, governmental, and otherwise; we might even feel that their flaws are connected in a broader sense. “The system itself is a failure,” the progressive activist Naomi Klein wrote, a few years ago, in her book “How to Change Everything.” Klein has argued that, in order to fight climate change, we need “system change”—a complete restructuring of the world’s economic arrangements in order to prioritize ecology over capital.

What do you do with a broken system? You gut it, scrap it, throw it out. Somewhat less radically, you may conclude that a person from outside the system, who owes it nothing, needs to come in and renovate it. (“The thing that scares the system, that scares the machine, is that Donald Trump is not a puppet,” Elon Musk said recently. “He’s a real person, and he’s not beholden to anyone.”) The failure of a system may make you feel that extreme actions are justified—perhaps not actions that you personally take but actions taken by others whom the system has failed more acutely. You may even come to believe that the system is broken because there is no system capable of handling the problem. In announcing the end of fact-checking efforts across Meta’s social platforms—instead, the company will rely on user-generated “community notes”—Mark Zuckerberg explained that “the problem with complex systems is, they make mistakes.” In his view, the mistakes involved in fact checking resulted in politically biased censorship, and were so problematic that it was better to make none at all.

It’s rhetorically powerful to argue that a system has failed. It clarifies things, or seems to, and it pushes us in the direction of dramatic, exciting action. In Hollywood movies, heroes go up against the system and win. (“The Matrix is a system, Neo,” Morpheus says. “That system is our enemy.”) People who seek power, or already have it, tend to say that they’re up against failed systems, even when they’re not. They can be persuasive because the structures that govern our lives are often so big and complicated that we can’t judge them instinctively. If you’re walking in the rain under an umbrella, and someone tells you that your umbrella is broken and tries to sell you a new one, you don’t even have to glance up to know if they’re right. But if someone tells you the sky is falling, you might wonder—Is it?

Of all the intuitions we have about system failure, the most potent is probably that when a system fails, it fails totally. This is sometimes true: a car’s engine, for example, can burn out, failing completely. But, when that happens, the engine has actually been failing for a while. Its parts have been wearing down, its oil has been running low, its ignition timing has drifted, its catalytic converters have clogged. It just needed maintenance, which is normal. Systems need maintenance because they are always failing, just a little; that is, they are failing and functioning at the same time. In the book “Thinking in Systems,” from 2008—a modern classic in the field of systems theory—Donella H. Meadows defined a system as “an interconnected set of elements that is coherently organized in a way that achieves something.” The elements often work against one another—that’s how a system keeps itself in check—and so their connections always need tuning up. But just because a system needs adjustment doesn’t mean that it’s failed. In fact, if a mechanic looked at an engine that needed a tune-up and declared that it was irrevocably damaged, he’d be the one failing. Failure is not a binary state.

Unlike engines, which sit tidily contained beneath their hoods, the systems that matter most to us are vast, and include people who work and live inside them. We ourselves live inside them, and experience how much they shape and even control us. And so another common intuition is that it’s people who stand outside of systems who are best positioned to fix them. Clearly, it’s the case that a person can be captured, pushed around, or brainwashed by a system. But it’s also important not to draw too hard a line between what’s on the inside and what’s on the outside. If you’re sick, your doctor gives you antibiotics, and the sickness goes away; it’s tempting to say that the cure came from outside your system. But, in fact, many antibiotics succeed by slowing down the growth of an infection to the point where the body’s own immune system can deal with it. The intervention from outside enables a solution from inside. If a doctor can’t fight an infection by working with the body, but only by hacking it up, then you might question his strategy.

Many systems possess internal mechanisms for regulating their own behavior; ironically, these mechanisms can be powerful enough to cause a system to lose control. In an extreme case of COVID, for example, a person’s immune system can respond to ravages in the lungs by flooding them with virus-fighting cells that summon more cells, which summon still more, creating a runaway feedback loop that results in deadly inflammation. By intensifying quickly, feedback loops allow a system to respond with force and speed; they also make it possible for an extreme outcome to result from a system that’s just a little unbalanced. Yet this in turn suggests that many extreme outcomes stem from small misadjustments in a system. In her book, Meadows explores a few different ways in which systems can end up consequentially off-kilter because of slightly misaligned parts: one element might be a bit too slow to send feedback to another (the time between arrest and trial might be too long); there might be too much or too little inventory held in a “buffer” (excess stock in a warehouse, say); because of what’s called bounded rationality, different parts of a system might end up pursuing goals that make sense at the local level, but not at the global one (teachers might begin teaching to the test). These marginal failures of fit can become a big deal when feedback loops take over. But they’re not hard to fix. When working with a system, it’s important not to assume that the scale of the problem implies the scale of the solution.

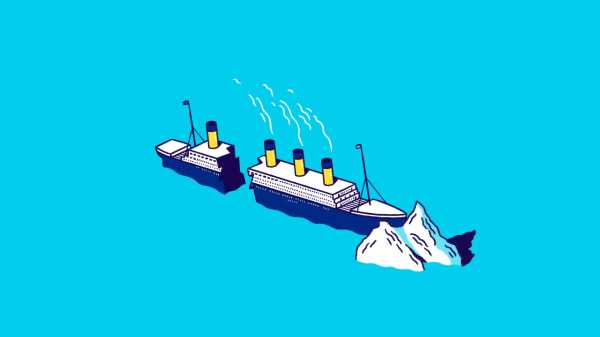

You may be familiar with the ship of Theseus—the ancient philosophical puzzle that asks you to imagine replacing the planks of a wooden ship, one by one, in the course of decades. If, eventually, every plank has been replaced, are you still sailing in the same boat? In 1913, the Austrian economist, sociologist, and philosopher Otto Neurath proposed a parallel idea, known as Neurath’s Boat. “We are like sailors who on the open sea must reconstruct their ship but are never able to start afresh from the bottom,” he wrote. The ship needs to be repaired, adjusted, and remade, but this must be done while it sails. This means that the work of altering the ship has a certain character: “Where a beam is taken away a new one must at once be put there, and for this the rest of the ship is used as support.”

Systems, famously, are resistant to change. If you mess with one part, you risk messing up the others, and this interdependence amounts to a pressure to keep things as they are. When we say that a system is broken, we sometimes mean that it’s imperfect and seems hopelessly difficult to modify. But another way of looking at this is that we’re on one of Neurath’s boats. The boat is hard to alter precisely because it’s sailing; the system is hard to change because it works. This doesn’t mean that we don’t want to change the system—but it does mean that we should interpret its resistance differently, not as a sign of failure but as an indication of usefulness. Repairs are harder mid-voyage. That shouldn’t make you want to burn your boat.

Anyone who has worked on a car, tended a garden, or written a computer program can tell you that systems are complicated, and always leaking, dying, or coming undone. Only novices believe that a system will work flawlessly. But it’s hard to be sanguine about systems, because their failures wound us, or worse. When a system fails you—when your taxes go up, when your claim is denied, when your hydrants run dry—the complexity of the system is no consolation. One of the awful things about living in a world ruled by systems is that brutal outcomes emerge from them.

Some apocalyptic narratives, like “Squid Game” or “The Purge,” imagine horrifying systems that are actually designed to produce brutal results. These stories are captivating because they reflect how much a system can hurt us. But they are not—obviously—accurate depictions of what most systems are like. They don’t explore the complex reality of systematized life, with its mix of standards-raising rationality and indifference to individuals; they dramatize the negative number on the right side of the equation, but not the sprawling formula on the left. A novel like Kafka’s “The Trial,” with its anterooms leading to courtrooms that pass cases on to higher courts, evokes the swirling complexity of systems that make us feel powerless. But most real systems are less abstract: we can pass laws that change how our courtrooms work.

An alternative to fantasizing about evil, all-powerful systems is imagining that they’re fundamentally simple. It’s possible to think that, at the end of the day, the apparent complexity of our systems is just a lot of hand-waving, and that they can be fixed quickly by someone with the right values or enough common sense. The dream is that you might identify the people who are messing everything up and tell them, “You’re fired!” But changing the components out of which a system is made, Meadows argues, rarely alters it fundamentally. “If you change all the players on a football team, it is still recognizably a football team,” she writes. (It might play better or worse, but it will still be a bunch of huge men tackling one another.) “The university has a constant flow of students and a slower flow of professors and administrators, but it is still a university,” she goes on. “In fact it is still the same university, distinct in subtle ways from others.” A system, she concludes, usually stays the way it is “even with complete substitution of its elements—as long as its interconnections and purposes remain intact.” It’s the ship of Theseus and Neurath’s boat, combined.

Actually changing a system involves reckoning with its myriad interconnections and its larger purpose. Who will define the purpose of a system, and who will do the adjusting? To whom are the adjustors accountable? How much time will elapse before we can see and judge the results? There’s a disconnect between the urgency with which we want our systems to change and the elaborate, detailed, and lugubrious process through which systemic change happens. The disconnect is both intellectual and affective: our desires need both to be translated into messages that systems can hear, and to cool to the temperatures at which they operate. “We can’t impose our will on a system,” Meadows writes. “We can listen to what the system tells us, and discover how its properties and our values can work together to bring forth something much better than could ever be produced by our will alone.” These words sound touchy-feely, but they aren’t. They describe a harsh reality, which we need to accept if we’re to make our world better. ♦

Sourse: newyorker.com