Save this storySave this storySave this storySave this story

Clegg’s hunt raises questions about online privacy, intellectual property, and what we aim to get out of social media, either as producers or consumers.

Memes have become part of Internet life. In the late nineties, a GeoCities Web page titled Hamster Dance featured rows of GIFs of rodents dancing to a sped-up version of a song from Disney’s “Robin Hood”; recent memes include the Disaster Girl, an image of a young girl smirking in front of a burning building, and the self-explanatory Kamala Harris Laughing. As these works of creativity become viral sensations—by being repeatedly clicked, copied, and shared—they can lose any connection to the person who dreamed them up. When the filmmaker Hugh Clegg, a recent graduate of England’s National Film and Television School, found that a video he had filmed of a friend and posted to YouTube had been reëdited and shared—widely—without giving him any credit, he launched a search.

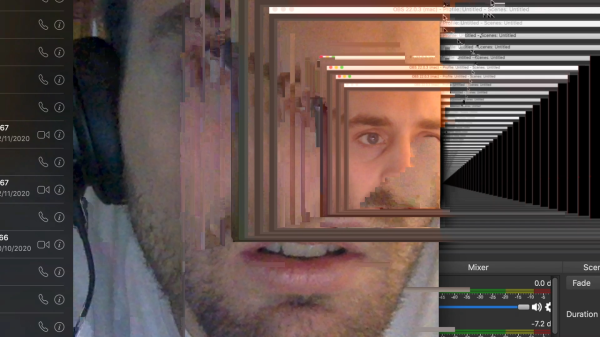

In 2019, Clegg produced a video showing the friend, who is a dead ringer for the former Prime Minister Boris Johnson, tackling an innocent bystander on the street. Not long after posting it, Clegg started receiving messages from a friend about seeing a clip of his original video going viral on TikTok, with one user getting tons of engagement from the snippet. The account was anonymous, and Clegg decided to investigate and find the user Mr_Bee_143, who had been sharing the video without crediting him. The narrative of this desktop documentary—a style of filmmaking that sources its imagery from the Internet through screen-capturing software—tells the story of his quest for the real identity of the person who reposted the video. The TikToker initially ignores Clegg’s entreaties while the video keeps collecting clicks, and the anonymous user seems like some kind of shadowy content thief. Soon Clegg’s digital chase becomes an emotional roller coaster.

The New Yorker Documentary

View the latest or submit your own film.

Clegg told me via e-mail that the pursuit “elicited so many emotions: embarrassment at not thinking of the meme idea myself; my fragile creative ego was bruised a little; anger at the lack of credit.” But, at the same time, it felt good to see that the video he had produced was gaining such traction, a sense of “flattery at so many people seeing my work.”

In the documentary, Clegg uses a stream of edited images and YouTube videos, and recordings of his video chats to take viewers along on the search. Sometimes that search is literal: screen grabs show him typing keywords into Google. “I found [that] portraying myself as being stuck within a screen more accurately showed the powerlessness of the situation,” Clegg mentioned.

The advice of a private detective soon leads Clegg to a social-networking platform for gamers, where the TikToker also has an account, and Clegg enters a virtual world where users represent themselves with avatars. The investigation yields a figure quite different from the nefarious scammer one might have imagined, and along the way Clegg’s hunt raises questions about online privacy, intellectual property, and what we aim to get out of social media, either as producers or consumers. “In making this film, there was definitely an aspect of giving some order to a very strange situation,” Clegg told me. “I don’t think I knew I was doing that at the time, but looking back it must have been a motivation. I think that’s why I make films, to give some order to a chaotic existence!”

Sourse: newyorker.com